MELANCOLIA, ALEGORIA E FRAGMENTO

Mísula

Espanha

Séc. XIV

Se no Romantismo o que conta é o símbolo, no Barroco o que figura é a alegoria. E alegoria vem aqui a dar-se como estado ruinoso, fragmentado. No barroco existe a melancolia, é o estado melancólico, como sentimento, que vem concluir a apoteose final de qualquer drama barroco. O mundo não pode mais parecer firme, não mais simplificado mas antes complexificado na sua forma fragmentada, ruinosa. O melancólico revê-se nesse mundo de bocados, de parcelas: fragmentos de estátuas e de colunas encontram-se pelo chão, ao lado das ornamentais caveiras. “Quando, no drama trágico, a história migra para o cenário da ação, ela fá-lo sob a forma da escrita. A palavra “história” está gravada no rosto da natureza com os caracteres da transitoriedade. A fisionomia alegórica da história natural, que o drama trágico coloca em cena, está realmente presente sob a forma da ruína. Com ela, a história transferiu-se de forma sensível para o palco. Assim configurada, a história não se revela como processo de uma vida eterna, mas antes como um progredir de um inevitável declínio. Com isso, a alegoria coloca-se declaradamente para lá da beleza. As alegorias são, no reino dos pensamentos, o que as ruínas são no reino das coisas. Daqui vem o culto barroco da ruína”(Walter Benjamin). A alegoria explica imediatamente, uma vez que o código de configurações possíveis (compreensíveis sempre através de um defeito de linguagem) se encontra limitado ao que a “história”, ou mais especificamente, o momento histórico, vem a representar. Na alegoria não existe a claridade do símbolo, não ganhando aquela, em expressão, aquilo que alcança em abstração. A forma figurada dá-se no imediato mas ela corresponde apenas à interpretação possível de um momento e não à força eterna do símbolo. A alegoria não passa pela ideia, mas faz valer tudo no fragmento dessa ideia. Daí que o melancólico encontre, na penumbra da figura destruída, o seu correlato. No barroco não é o melancólico que faz a figura valer enquanto imediato, é a figura que, por ser fragmentação da ideia, encontra no sentimento do melancólico a lei da sua possibilidade de existir. O defeito na linguagem da alegoria vem alimentar o espectro melancólico por momentos sempre breves mas acumulados. Na aparência, a forma primeira desliga-se do que quer ser e esta distância aviva a natureza trágica do melancólico que se encontra cercado de muitas figurações do possível. A “história” vem aqui a dar lugar a uma separação porque ela vem acentuar o carácter fragmentário da sua continuidade. A alegoria é já ruína da “história” e o seu movimento só pode ser decadente, tendendo para o fim. Daí o gosto barroco pela apoteose e o gosto melancólico pela elegia. Porque não é tanto dentro de si que encontra os seus correspondentes (a não ser que estes correspondentes sejam heterónimos). Talvez que ao melancólico nem mesmo interesse que hajam correspondentes. A escolha da elegia como forma literária característica encontra todo o seu valor na dedicação, no encontro com a distância, na contemplação pela forma fragmentada que ao reunir-se num todo torna esse todo num híbrido e irreconhecível a uma primeira observação, ou seja, um todo enigmático.

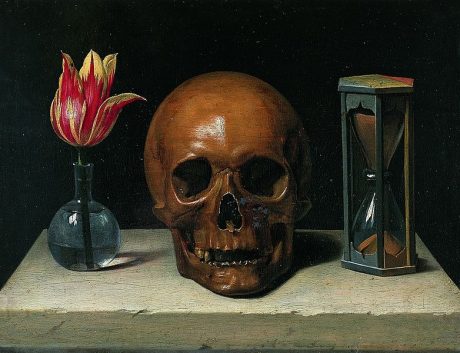

Philippe de Champaigne

Natureza Morta com Caveira (Vanitas )

1671

óleo sobre painel

28 x 37 cm

No barroco o objecto encontra-se fragmentado e é no fragmento que o melancólico vem encontrar a sua identificação ou identidade. O suporte do melancólico não é outro sujeito, como na amizade, mas o objecto que se encontra ruinoso. Só neste encontra correspondências. Primeiro, pela distância em relação à totalidade da ideia que não se encontra toda, ou seja, plenamente, na ruína. Depois, porque essa distância se torna toda ela efetiva, ou seja, participativa, mesmo na inatividade, ou seja, na pura contemplação. Esta relação vem afastar o melancólico do dado empírico. Porque se alimenta de um defeito da linguagem, de uma distorção que parte do objecto como entidade plena, digna de legislar sobre esse melancólico. Assim se abre um mundo de linguagem rarefeita, fragmentada, que divide o sujeito que se guia pelo objecto alegórico. O objecto vem a comandar o sujeito, obrigando-o a atingir constantemente um limite, que não é um pico como numa hipóstase, mas uma força que percorre um campo objectivo. À força dos sentidos está ligada apenas a contemplação desse objecto ruinoso, que apela ao sentimento mais que ao reconhecimento: “O luto é o estado de alma em que o sentimento reanima o mundo vazio apondo-lhe uma máscara, para experimentar um prazer enigmático à vista dele. Todo o sentimento está ligado a um objecto apriorístico, e a representação deste é a sua fenomenologia. A teoria do luto, tal como ela se ia delineando enquanto contraponto para a tragédia, só pode, por isso, ser desenvolvida através da descrição daquele mundo que se abre diante do olhar do melancólico. Pois os sentimentos, por mais vagos que possam parecer à autopercepção, respondem, como um reflexo motor à estrutura objectiva do mundo. Se as leis do drama trágico lutuoso se encontram no âmago do próprio luto, em parte explícitas, em parte implícitas, a sua representação não se destina ao estado afectivo do poeta nem ao do público, mas antes a um sentir dissociado do sujeito empírico e intimamente ligado à plenitude de um objecto”(Walter Benjamin). O sentimento encontra o seu alheamento no interior de um estado afectivo se apelar ao reconhecimento. Ao partir-se de um objecto como ponto de partida para a melancolia, convém que esse objecto, apesar de ruinoso, se encontre configurado. E só o está se nele percorrer um certo sentido do momento histórico. Pois só este pode concorrer, pela sua grandeza, com o poder infinito da pequenez de um objecto fragmentado. Por outro lado, não vem a história afectar um olhar contemplativo. Mas é o objecto que, na sua infinita pequenez contrasta com aquela grandeza, de tal maneira implícita, que o objecto se encontra sempre na sua “plenitude”. No barroco, a história é um domínio raro, toda a origem provém da ordem em que os objetos se prestam à contemplação. Mas se a história é decadência é porque os objetos se encontram arruinados, mas encontram-se, assim mesmo, na sua objectividade máxima. Ora isto tem que ver mais com um conhecimento (não empírico) que com um reconhecimento, por parte do melancólico. Esta distinção entre o “histórico” infinitamente grande e o alegórico infinitamente pequeno parece revelar de uma dialéctica que invade o centro das ideias do melancólico. Corresponde para Walter Benjamin, a uma teoria do conhecimento (“A new methodology and theory of knowledge”(Beatrice Hansen)) em que o objecto invade enigmaticamente o sujeito que se liga ao mundo, não empiricamente, mas apenas pela via da contemplação. Corresponde a um sistema de conhecimento de um objecto constitutivo do sujeito: o fragmento. O fragmento dá-se numa potenciação e penetra no sujeito melancólico que o conhece através da imersão nesse objecto. Mas como é possível descrever a “imersão” que o objecto provoca no melancólico? Sem dúvida que não é pelos sentidos. Estes estão demasiado dogmatizados, demasiado racionalizados. A “imersão” dá-se a partir da abertura do sujeito a uma nova ordem que não é a dos conceitos (tanto quanto a figuração alegórica deles se dissocia, pela fragmentação dos mesmos): “Porque toda a sabedoria do melancólico obedece a uma lei das profundezas; a ela obriga-se a partir do aprofundamento, na vida, das coisas criaturais, a voz da revelação é-lhe desconhecida. Tudo o que é saturnino remete para as profundezas da Terra, pois é aí que se conserva a natureza do velho deus das sementeiras. Segundo Agrippa von Nettesheim, Saturno concede aos homens as “sementes das profundezas e…os tesouros escondidos”. Os olhos postos no chão caracterizam aí o saturnino, que perfura a terra com os olhos” (Walter Benjamin).

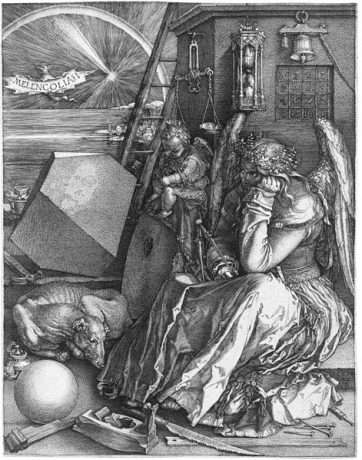

Albrecht Dürer

Melancholia I

1514

gravura

31 x 16 cm

A Terra oferece-se como sistema de múltiplos, que são os objetos alegóricos. Mas, mais profundamente, oferece um sentido de unidade ao sistema do contemplativo, porque oferece o conhecimento mais profundo, ou seja, mais interior, das próprias coisas, do próprio mundo. Que não hajam dúvidas quanto a uma ligação do ser melancólico com a Terra, já que esta deve “à força de concentração a sua forma esférica e, por conseguinte, como já achava Ptolomeu, a sua perfeição e a sua posição central no universo” (Walter Benjamin).Esta concentração precede a concentração melancólica e iguala-se a ela: a terra como sistema de conhecimento reflete um centro fragmentado de si mesmo que, quer como agonia, quer como puro ser trágico, aparece imperativamente ao melancólico, porque remete para uma interioridade inacabada, uma vez que o ser é atravessado pela terra aquando da sua contemplação, bem como pelas coisas, mas não totalmente, apenas de forma fragmentária, sendo que a outra parte pertence, sem adiamento, à ordem das ideias inacabadas que vem completar-se nas coisas: “À sua infidelidade aos seres humanos corresponde uma fidelidade às coisas, que verdadeiramente o mergulha numa entrega contemplativa. O lugar da caracterização adequada do conceito que espelha este comportamento só pode ser o dessa fidelidade desesperançada ao mundo criatural e à lei da culpa que governa a sua vida. Todas as decisões essenciais na relação com os homens podem ofender os princípios da fidelidade, elas regem-se por leis superiores. Essa fidelidade só está perfeitamente adequada à relação dos homens com o mundo das coisas. Este não conhece lei mais alta, e a fidelidade não conhece objecto a que mais exclusivamente pertença do que o mundo das coisas” (Walter Benjamin).

J.V.

««««»»»»

MELANCHOLY, ALLEGORY AND FRAGMENT

If in Romanticism what counts is the symbol, in the Baroque what appears as figure is the allegory. And the allegory appears as ruinous state, fragmented. In the Baroque there is melancholy, it is the melancholic state that, as feeling, comes to conclude the final apotheosis of any Baroque drama. The world can no longer look firm, no more simplified but rather complex in its ruined, fragmented form. The melancholic man sees himself in that world made of pieces, of parcels: fragments of statues and of columns are found on the ground, next to ornamental skulls. “When, in the tragic drama, the story migrates to the action setting, it does so in the form of writing. The word “story” is carved in the face of nature with the characters of the transitory. The allegoric physiognomy of natural history that the tragic drama places at the setting, is really present as the form of ruin. With it, the story was transferred sensitively to the stage. Configured in that way, the story is not revealed as process of an eternal life but rather as the progression of an inevitable decline. In this way, the allegory is bluntly placed beyond beauty. Allegories are, in the kingdom of thoughts, what ruins are in the kingdom of things. From here comes the Baroque cult of ruin” (Walter Benjamin). The allegory explains immediately, given the fact that the code for possible configurations (always comprehensible through a language defect) is limited to what the history, or more specifically, the historic moment comes to represent.

In the allegory there isn’t the clarity of the symbol. The allegory is more abstractive than expressive. The figured form is given immediately but it only corresponds with the possible interpretation of a moment and not with the eternal force of the symbol. The allegory does not touch the idea but is fully given in the fragment of that idea. Thus, the melancholic man finds, under the shadow of the destroyed figure, its correlative. In the Baroque it is not the melancholic man that makes the figure worth as immediacy but rather the figure that, being the fragmentation of the idea, finds in his feeling the law for the possibility of its existence.

The defect in the allegory’s language comes to feed the melancholic specter for brief but always accumulated moments. In the appearance, the form is first disconnected of what it wants to be and this distance revives the tragic nature of the melancholic man which is surrounded by the many figurations of the possible. The “history” gives place here to a separation because it comes to accent the fragmentary aspect of its continuity. The allegory is the ruin of “history” and its movement can only be decadent, tending towards the end. Thus the Baroque taste for the apotheosis and the melancholic taste for the elegy. Because it is not so much inside of himself that he finds its correlatives (unless they are heteronyms). Maybe that for him it’s not even interesting that there are correlatives. The choice of the elegy as characteristic literary form finds its whole value in the dedication, in meeting the distance, in the contemplation of the fragmented form that, being reunited in a whole, makes this whole an hybrid, unrecognizable to first sight: an enigmatic whole.

In the Baroque the object is fragmented and it is in the fragment that the melancholic man comes to find his identification or identity. The support of the melancholic man is not another subject, as in friendship, but the ruinous object. Only in this one does he find correspondences. At first because of the distance from the totality of the idea that is not fully given in the ruin an then because this full distance becomes effective or, in other words, participatory even through inactivity or pure contemplation. This relation sets the melancholic man apart from the empiric data because it feeds from a language defect, from a distortion that starts from the object as full entity, worthy for legislating on him. Therefore, a world of rarified language is open, fragmented language that splits the subject in two and is guided by the allegoric object.

The object commands the subject, forcing him to constantly achieve a limit, which is not a peak as in an hypostasis but a force running through an objective field. To the force of the senses is given just the contemplation of that ruinous object that appeals more to the senses than to recognition: “mourning is the soul’s state in which the sentiment revives the empty world by adding a mask to it, in order to experiment an enigmatic pleasure at its sight. Every sentiment is connected to an aprioristic object and this object’s representation is its phenomenology. The theory of mourning, in the way it used to be drawn as a counterpart for the tragedy, can therefore only be developed through the description of that world that opens before the sight of the melancholic man. Because feelings, as vague they may seem to self-perception, respond as a motor reflex to the objective structure of the world. If the laws of the mournful tragic drama are found at the core of mourning itself, in part implicit, in part explicit, its representation is not destined to the affective state of the poet or to the public, but rather to a feeling dissociated from the empiric subject and intimately connected to the plenitude of an object” (Walter Benjamin).

The feeling always finds its absentmindedness at the interior of an affective state if it appeals to recognition. By starting from an object as the melancholy starting point, it is convenient that that object, despite being ruinous, is configured and it is only configured if it runs through a certain sense of the historic moment which, because of its greatness, is the only one able to compete with the infinite power of the fragmented object’s smallness. On the other hand, history does not come to affect a contemplative look but it is the object that, in its infinite smallness, contrasts with that greatness, so implicit that the object can always be found in its “plenitude”.

In the Baroque, history is a rare domain. All origins come from the order in which the objects are offered to the contemplation but if history is decadence, it is because the objects are found already ruined. Nevertheless, they are in that way in their maximal objectivity. Now, this has to do more with a (non-empirical) knowledge than with a re-cognition on the melancholic man’s behalf. This distinction between the infinitely great “historic” and the infinitely great allegoric seems to reveal a dialectics that invades the center of the ideas of the melancholic man. It corresponds, to Walter Benjamin, to a theory of knowledge (“A new methodology and theory of knowledge”(Beatrice Hansen)) in which the object enigmatically invades the subject that connects to the world, non-empirically, but only by the way of contemplation. It corresponds to a system of knowledge of a subject’s constitutive object: the fragment. The fragment is given in potency and penetrates the melancholic subject that knows him through the immersion in that object.

How is it possible to describe the “immersion” that the object provokes in the melancholic? It is not, without a doubt, through the senses, which are too dogmatized, too rationalized. Such an “immersion” is given with the opening of the subject to a new order that is not the one of the concepts (as far as the allegoric figuration is dissociated from them, through their fragmentation): “because the whole melancholic man’s wisdom obeys the law of the depths, it is obligated to it through the deepening in life of creatural things, and the voice of revelation is unknown to it. Everything which is saturnine points to the depths of the Earth, because it is there that the nature of the old god of the crops is kept. According to Agrippa von Nettesheim, Saturn gives to men the “seeds of the depths and… the hidden treasures”. The eyes pointing to the ground are characterizing of the saturnine, who punctures the earth with his eyes” (Walter Benjamin).

The Earth is offered as a system of multiples, which are the allegoric objects. At a deeper level it offers a sense of unity to the contemplative man’s system, because it offers a profounder knowledge, more interior, of things themselves, of the world itself. There must be no doubts about a connection of the melancholic being with the Earth, since the Earth owes “to the force of concentration its spherical form and consequently, as already Ptolemy thought, its perfection and central position in the universe” (Walter Benjamin).

This concentration precedes the melancholic concentration and is equal to it: the earth as a knowledge system reflects a fragmented center which, whether as agony or as pure tragic being, appears imperatively to the melancholic man because it remits to an unfinished interiority, since the being is traversed by the land when he contemplates. He is also traversed by the things but not completely, only in a fragmentary way, while the other part belongs, without postponement, to the order of unfinished ideas that comes to be complete in things: “to his infidelity to human beings corresponds a fidelity to things that truly submerges him in a contemplative surrender. The place of the adequate characterization of the concept which mirrors this behavior can only be the one that hopeless fidelity to the creatural world and to the law of guilt that rules his life. Every essential decisions in the relation with men can offend the principles of fidelity, they are ruled by superior laws. That fidelity is only perfectly adequate to the relation of men with the world of things, which does not know a higher law, and it does not know a better object to which it exclusively belongs than the world of things (Walter Benjamin).

J.V.